Big-picture modelling & cheap surveys to ignore

Dominic Mills discusses the range of industry business models and despairs at another survey about lack of trust in advertising

For as long as I can remember, the industry has obsessed about its business models and their appropriateness. Of course, the discussion has moved on — from agonised deliberations about billable hours, one-stop shops and generalists vs specialists (although they linger still) — to broader questions about technology, over-arching creative platforms and in-housing.

My fellow columnist Nick Manning added his weight a few weeks ago with this tough piece on media agencies. COVID, he says, has exposed their fault-lines.

But technology, accelerated by COVID, has driven a new urgency. Hats off then to the IPA for its report last week on the landscape, a wide-ranging and useful piece of work.

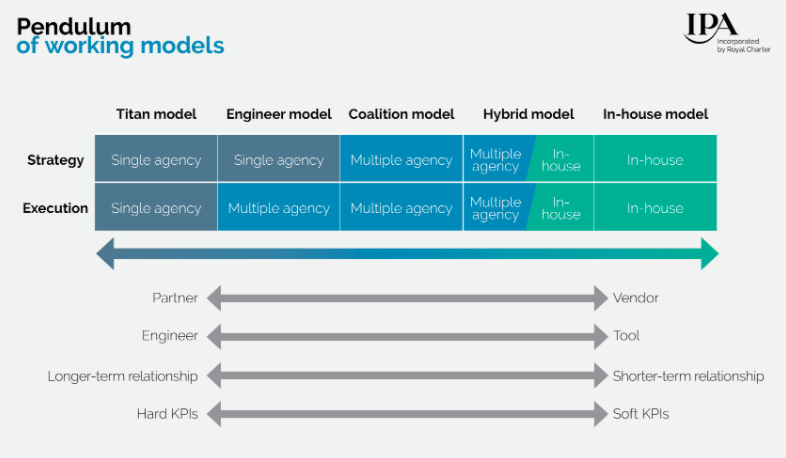

The IPA identifies five broad models: Titans, essential one-stop shops; engineers, which develop an overall strategy and leave the execution to others; coalitions, which require multiple agencies to develop and execute; hybrids, where the strategy is developed externally and implemented in-house; and the in-house model.

I imagine there are more than a few agency chiefs looking at this and asking themselves: “Where do we fit? And are we in a category positioned for growth?”

To me, one of the joys of the business is its collective capacity for reinvention and its willingness to find and exploit opportunity. There’s an energy and restlessness that is immensely refreshing, whether it takes the form of network mergers and collaborations (at WPP for example) or launches based on new iterations.

And never has the opportunity been greater, driven by that potent combination of client need and broader technological, societal and economic change.

You can see the evidence in the profusion of new agency launches over this year — of all years. There’s a good piece in Campaign covering this.

While they mostly differ — the client community is a broad church with many different needs to satisfy — there are areas of common ground.

This is around what you might describe as entities that are ‘structure-light and talent-heavy’. Speed and agility are prioritised over process, and the establishment of these new entities is made possible by the availability of experienced talent — many of whom are network refugees — who want to work in new ways and whom technology allows them to do so unconstrained by geography.

One of the more interesting examples is Blitzworks, which promises to offer clients a creative platform in just three days using a rapid-turnaround improvisation model, based on collaboration and seasoned creative talent.

Its founders are three ex-network executives, Marcus Brown (Y&R) and creatives Ajab Samrai (Saatchis and Ogilvy) and John Pallant (Saatchis), with the ability to tap into a squad of different talents covering strategy, media, digital design and production. I dare say their experience has coloured their view of more traditional models.

One client is Diageo, which suggests Blitzworks’ appeal isn’t just, as one might expect, to digital start-ups or direct-to-consumer brands.

For me, the real point of tension is between these new types of agency and the growth of the in-housers.

For its part, the IPA sees the higher-growth areas as engineers and hybrids, but only moderate growth — albeit better in the short term — among the in-housers.

Generally these new agencies seek to complement rather than compete with the in-housers, and not just because the in-housers are more likely to require resource and process.

The in-housing trend has still to play out fully. We mostly hear of its growth, but there are still many unanswered questions. Is it sustainable? Is it cost-efficient, especially in a downturn? And most importantly, is it effective?

However it evolves, it has profound significance for agencies, whether networks, hybrids, virtuals and start-ups.

Cheap survey, cheap headline

Collectively, the ad industry is prone to bouts of self-doubt and self-flagellation. I think this stems from its inherent desire to people-please. And when the people aren’t pleased — yes, there are those who hate advertising — the industry beats itself up.

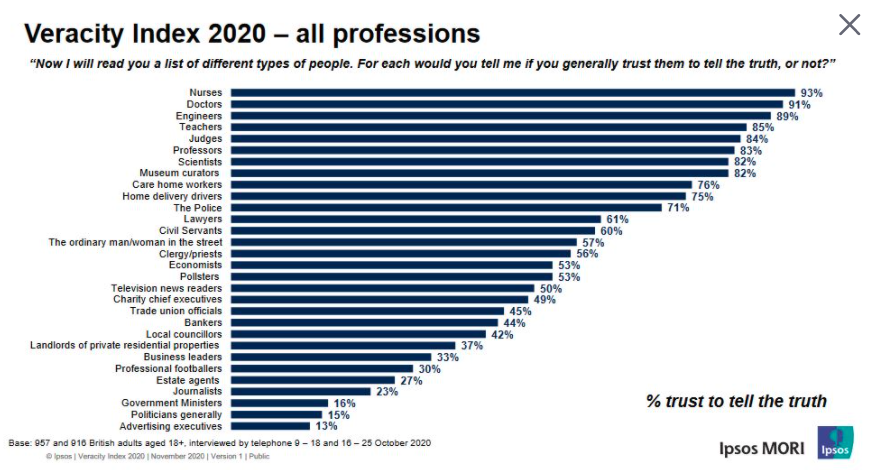

And what better reason than yet another survey, published last week, in which the industry again tops (in an inverted manner) the table of least-trusted professions.

And let me be open: I find these surveys unbelievably irritating, and not just because journalists and ad people perform poorly in the public opinion.

You can read it here. It’s got a faux-posh name — The Veracity Index — to give it a smear of credibility.

But don’t be fooled. It’s a cheap survey designed to garner — which it invariably does — cheap headlines.

I won’t go into detail, but the survey is based on the question: “For each [eg lawyer, civil servant, advertising executive], would you tell me if you generally trust them to tell the truth or not?”.

Both the question and the list of job functions are one-dimensional and the results, therefore, are profoundly predictable: this year’s list is topped by those who’ve had a good COVID — nurses, doctors, teachers and so on — and tailed by the usual suspects — government ministers, politicians, journalists and ad-folk.

There’s a slightly surreal element to the choice of some categories — museum curators (6th) for example. And home delivery drivers (8th): do they mean those from Tesco and Ocado (with whom my experiences are universally positive) or DPD and Dodl (with whom they’re not)?

Which leads us to the question: so what?

In the case of ad execs, is the question really about them or the ads? And let’s not even get into a debate about what constitutes an ‘ad executive’.

But where the survey falls down, if you’re feeling nit-picky, is that it fails to represent the client community for whom the advertising industry works and on whose behalf it tells the truth or not.

You can certainly think of some client categories that have not had a good COVID: airlines for example. Depending on experience, some might add mortgage lenders, insurers, supermarkets, mobile phone companies, utilities and so on.

But all this is covered under ‘Business leaders’. Hopeless.

My vow therefore is to stop reading and writing about these surveys. I suggest the industry ignore them too.