Black history brands & Halifax gets ‘human’

Dominic Mills questions why there’s still outdated brand iconography on UK supermarket shelves and could brand ‘humaning’ be catching on?

It’s Black History Month in the U.S and doubtless, brands and agencies will be running awareness sessions while at the same time asking themselves if there is a topical advertising or marketing theme they can adopt — or, indeed, whether it is better to stay low.

Some Super Bowl advertisers already seem to have fallen at the first hurdle, according to this analysis. It says many failed to pass muster, not just on diversity casting but also in cultural relevance.

One brand that wasn’t at the Super Bowl but has been especially late to the diversity party in the U.S is Aunt Jemima, a PepsiCo-owned syrup and pancake mix whose eponymous icon — the slave mammy stereotype — has featured both on the packaging and in its ads over the years.

This week — and for the life of me I can’t work out if the timing is good or terrible — PepsiCo announced that Aunt Jemima was going and the brand would henceforth be known as Pearl Milling Company. That is a dull, dull name but I guess PepsiCo has erred on the side of caution.

What I can’t get over is how PepsiCo — and previous owners — stuck with the name and icon, not just through the Civil Rights movement of the 60s and 70s, but right up until June last year and the wave that was (and is) Black Lives Matter, at which point it decided enough was enough.

[advert position=”left”]

Perhaps, in an upside-down kind of way, it thought that the brand was so powerful it couldn’t afford to drop it. Maybe also, it’s the sense of familiarity which deadens consumer senses to the wider context.

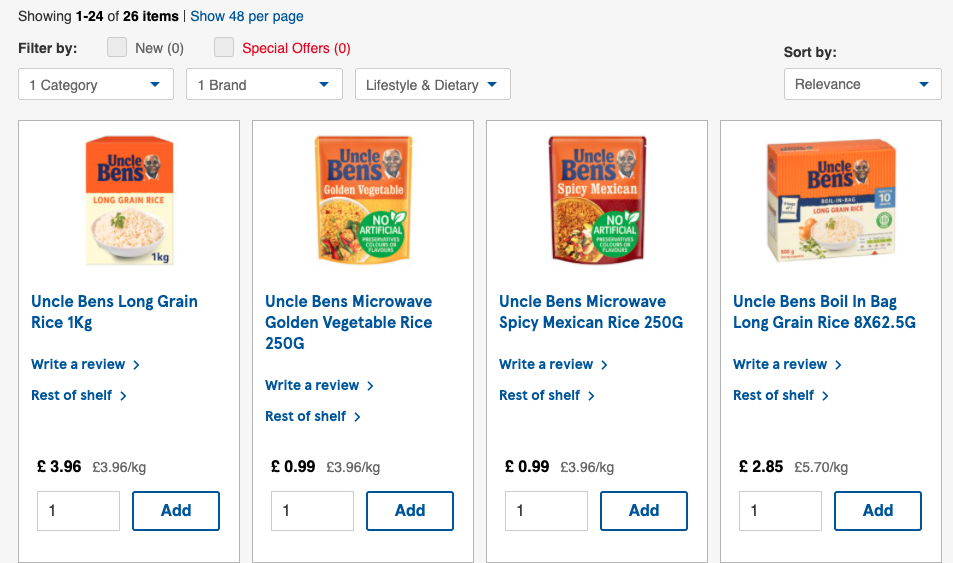

I can only think that explains how for years, I looked at a box of Uncle Ben’s in the cupboard and didn’t give it a second thought. For Uncle Ben’s, which features a genial-looking, bow-tied black man of about 50-60 — he could be a waiter or a butler — is equally based on a racial stereotype.

Uncle Ben’s owner Mars has at various times said Ben was either a black rice farmer, a chef or a Chicago waiter. Whatever he was, he was effectively positioned as a servant-type figure.

Nevertheless, last year — 30, 40, 50 years too late — it gave up the pretence and decided that in future it would be called Ben’s Original, accompanied by ritual corporate hand-wringing, a promise to “create opportunities that offer everyone a seat at the table” (no idea what that means), and a cash bung to black communities to help salve its conscience.

But its conscience appears to be weirdly lacking in the UK. A search of its UK recipe website shows the product is still called Uncle Ben’s, complete with the standard iconography. Supermarket shelves still carry the product with the original logo.

This is a puzzle. Black Lives Matter is a force here and indeed the UK, with both its imperial past and its pivotal role in the slave trade with the U.S, is a country increasingly sensitive to its historical role in colonial exploitation.

And while ‘empire’ brands still exist — tea, for example (although I’m not sure Imperial Leather soap counts), or HSBC with its tangential involvement in the 19th century Opium Wars — they don’t seem to make much of their roots.

It’s odd in one way, because provenance is a powerful differentiator, but perhaps suggests they got wise early on and, not to put too fine a point on it, airbrushed the less agreeable aspects of their history away.

That is not to say it hasn’t happened in the past. I can’t find it, but I remember a Kenco ad in which the man from HQ visited the coffee plantations in, say, Kenya where he was greeted with joy.

Del Monte is not a British brand, but even up until the mid 90s, British ads featured a man in a white suit telling the happy natives their fruit was good enough to harvest.

And so good was the idea, apparently, that the cool fella was brought back in 2018.

Nothing however, tops the combination of British imperialism and casual racism of this Silk Cut ad, a parody of the film Zulu.

At the time, it was wildly popular. But now it’s beyond excruciating, best watched through your fingers.

But there is no accounting for taste or logic sometimes.

A beer brand called British Empire, launched in 2011 and clearly playing the nostalgia card, has for the past two years sponsored the Indian Premier League cricket team Chennai Super Kings, the Liverpool or Man City of that particular competition.

The twist is that British Empire is owned by a local Tamil brewery. Twist #2, if you’re interested, is that alcohol brands aren’t allowed to advertise in India. Weird or what.

The, er, ‘humaning’ of Halifax

I’m always suspicious when brands decide they are all about people. I mean, what were they up to before if it wasn’t about the people who were, or could be, their customers?

While I wouldn’t say Halifax in its new campaign has gone the full Mondelez and discovered ‘humaning’ like it’s the elixir of brand positioning, there are shades of similarity.

Here’s the official statement, which describes the move thus:

“Halifax is re-launching its brand positioning to be all about people…..The ‘It’s a people thing’ campaign sets a direction for the entire brand, built around the simple belief that banking at its heart is people helping people.”

Anyway, small gripe over…here’s the ad.

And what can you say? The Oasis soundtrack grabs you from the start and leads the viewer into a normal-looking British street (but by no means typical, I’d say, because if it’s in London those houses would easily be in the £1 million+ bracket) where we see the various residents experiencing joy and sadness.

Very slice-of-life, very populist. “Halifax: it’s a people thing”, the end-line concludes, a bit bleedin’ obviously IMHO.

And yet, curiously warming — how refreshing to see ordinary life portrayed for once — and true to the brand. That’s because, of all the banks, I’d always thought of Halifax as the most down-to-earth and mid-market in its stance.

And while I find the overall picture a little puzzling — is there really a gap in the market? All banks have gone out of their way to show us they’re on our side, none more so than Halifax’s parent Lloyds

I think the real interest will be not so much in the ad as in how the ‘people thing’ plays out in real life.

Which is why the choice of New Commercial Arts (NCA) as the agency is so pertinent.

NCA has set its stall out as combining populist advertising with the hard yards of customer experience. If Halifax fails to deliver on the latter, then all the work of ad is for nothing. Both parties have a lot riding on this project.