The inflation test; false causation & a graduation party

Dominic Mills looks at the impact of rising inflation on media, pokes Ben & Jerry’s for a poor performance in Wolff Olins’ Conscious Brands report and salutes a graduate trainee

The BBC news on Sunday had an item, illustrated by footage of a Travis Perkins building yard, about the spectre of rising consumer price inflation (CPI) and its impact on our pockets. In fact it’s already here: UK CPI doubled to 1.7% in April from 0.5% in March, driven to some extent by higher oil and gas prices.

But as GroupM’s Brian Wieser pointed out a month ago, staples critical to food products have also doubled in price in a year — in this case soybeans and corn — meaning it’s not just building products or, indeed, rare earth mineral prices causing a shortage of microchips.

Add in higher transport costs and our prolonged spell of low inflation may shortly be a thing of the past.

How does this matter to brands and advertising?

Well, food and packaged goods manufacturers, to take two examples, will only have a limited appetite for carrying these extra costs. At some point they will look to pass the costs on to retailers and, ultimately, consumers.

Consumers meanwhile will either be looking for lower-cost substitutes or reasons to stick with more premium products.

Which is where the power of the brand comes in.

As countless IPA effectiveness studies have shown, a powerful brand is a singular tool in the ability of manufacturers to defend or raise prices or drive loyalty.

Those who have consistently spent on their brand therefore — the likes of Unilever, Diageo, Reckitt and so on — are in a better position.

It’s too late in the cycle for those manufacturers who have neglected their brands to start pumping money into, say, TV or OOH, to negate current inflationary trends. But not necessarily for the future. Except that it’s not just palm oil and soybean prices that are rising but also UK media costs — 3.4% overall and 7% in TV and 5% in OOH. Tough one.

Woke-ism and the danger of false causation

If I worked for Ben & Jerry’s I might well be spitting mad this week. All its efforts to portray itself as empathetic and highly moral (woke, to me and you)… they’ve come to naught.

How do I know? According to the latest index of brand purpose, aka the Top 100 Conscious Brands Report from Wolff Olins, Ben & Jerry’s comes 62nd in the UK and 57th in the US.

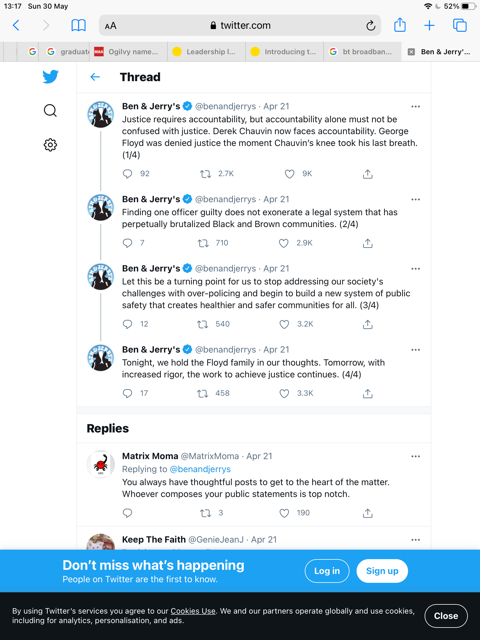

So… taking on Priti Patel and handing out Cherry Garcia to cross- channel immigrants as they land, or renaming its Coconutterly Caramel’d non-dairy flavour to Save Our Swirled Now! in a bid to urge UK leaders to tackle climate change and berating the US justice system after the conviction of Derek Chauvin… it’s clear moral supremacy gets you nowhere.

Worse, B&J’s was beaten by the likes of Microsoft, Google, Pfizer, Amazon, Astra Zeneca, Intel, Disney and YouTube, all of which figured in the top 20 rankings in the US and UK.

Big Tech and Big Pharma are more ‘conscious’ than B&J’s? Outrageous.

How could this be? I’m not sure, except that B&J’s is clearly failing on some of the six measures Wolff Olins identifies as markers of conscious brands: Empathy; multi-sensory; habitual; reformist; collective; and moral.

Either that or the 9,000 consumers surveyed for the study don’t buy the B&J’s purpose act.

But to a more serious failing in the report: false causation.

According to Wolff Olins, the top five scoring brands experienced an average 17% revenue growth in 2020. The bottom 15, by contrast, experienced an average fall of 9% in revenue growth.

I’ll take the maths as correct but that’s about it. The UK and US top fives comprised Microsoft, Google, Glossier, Amazon, YouTube, Headspace, the BBC and Astra Zeneca.

To suggest that their revenue growth was down to their status as conscious brands is either downright naive or a slippery attempt to convince the hard-hearts to get with the Big C plan.

Equally, the figures are equally loose the other way. Among those in the bottom 15 were brands that clearly were hit by the pandemic — Airbnb, VW, Uber, HP, Starbucks.

I’ve seen this before, notably with other studies that have linked the purpose with share prices, conveniently forgetting that — as most certainly with financial performance in 2020 — many other more important factors are in play.

[advert position=”left”]

It’s dangerous to those who take these things seriously, and it makes the authors look daft too.

One more thing: It’s a good idea for anyone that claims, as Wolff Olins does, “to help create the world’s most transformative brands”, to be able to spell Proctor and Gamble [sic] correctly: the second ‘o’ is an ‘e’….

An old-fashioned promotion

There’s something thrillingly old-fashioned about the promotion last week of Fiona Gordon to chief executive of Ogilvy UK, covering the main agency and all its sister companies.

I say that not just because she is a company lifer, but because she is that rare creature, a graduate trainee who joined the agency in 1992: that really is call for a graduation ceremony.

Of how many graduates can you say not only that they have lasted the course with the industry and their original employer, but risen to the top?

It almost certainly won’t happen again. Graduate trainee schemes of the type that Gordon joined seem to be more or less — with honourable exceptions like WPP and Ogilvy — a thing of the past.

Contrary to my expectations, graduate schemes are not entirely dead but today’s versions, judging by Student Ladder, are smaller, shorter and more akin to enhanced internship programmes.

Gordon’s rise reflects well both on her and the Ogilvy scheme itself, but the chances of today’s graduates enjoying a similar career — which has included spells in Asia and the US — are minuscule.