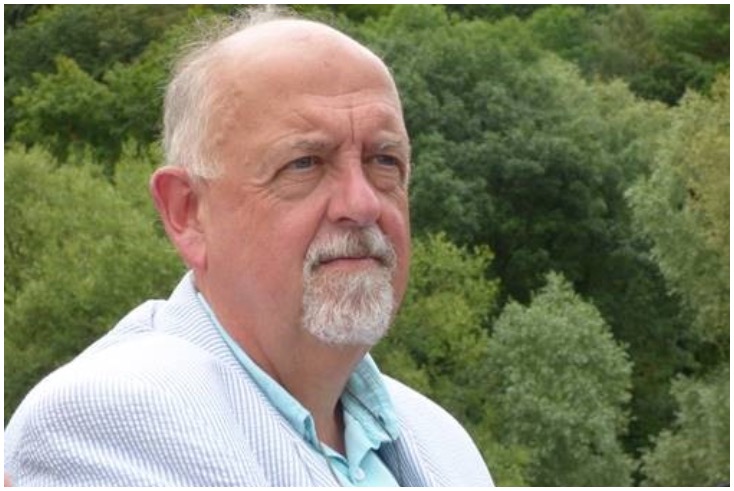

Making Sense of it All: Paul Feldwick says media and creative reunion is overdue

Creative and media people would serve brands better by coming back together in agencies, the author and leading strategy thinker Paul Feldwick has suggested.

In the latest episode of Mediatel News‘ “Making Sense of It All” video series, Feldwick explains how the need to build brands while also responding well to advertiser data is being held back by creative and media agencies operating in silos.

He says: “The planners were the people who were pulling all the data sources together and interpreting it and helping to make sense of it which is which is precisely what we’re doing now… bringing creative and media back together is something that is probably overdue.”

In this interview with Brian Jacobs, partner at Crater Lake & Co, Feldwick also argues:

- CMOs face an increasingly difficult challenge in convincing their company leadership to invest in brand-building as opposed to short-term marketing tactics

- the professionalisation of the advertising industry has created a divide between what is popular versus what is “creative”

Paul Feldwick was formerly head of account planning at BMP and is the author of two books, The Anatomy of Humbug and Why Does the Peddler Sing?

Watch the video below or read a full transcript further below

Making Sense of it All is weekly video interview series by Mediatel News in association with Crater Lake & Co. Each Tuesday, we publish interviews with the industry’s most thought-provoking marketers, agency executives and research thinkers to find out how people working in media can make sense of this ever more complicated and fragmented ecosystem.

Transcript

BRIAN JACOBS: Paul, in your books you’ve talked about how advertising seems to have lost its way by becoming a bit disconnected from popular culture. What do you think that’s down to? Is it down to a lack of appreciation of what’s happening in popular culture or are we becoming too inwardly obsessed about our own business? What do you think is behind that?

PAUL FELDWICK: I think it goes right back to about 1900 when the modern advertising agency started to take itself seriously and wanted to look professional. Right from that date you can see how agencies really wanted to differentiate themselves and distance themselves from the mountebanks and medicine shows and impresarios who who are in many ways their their their antecedents so that by 1910 (as early as that!) the trade magazine Printers Inc refused to celebrate the centenary of PT Barnum’s death because they said he stood for everything that modern advertising was not. It was vulgar, it was bizarre, it pandered to the lowest of the low and all this sort of thing.

And in its place they built this dominant discourse about how advertising works which is that it’s not about entertainment; it’s about serious selling, it’s about giving facts and it’s about rational persuasion. That has continued to be very dominant. Ever since, in many ways, despite the fact that as media developed, of course, the industry was inexorably drawn back towards the worlds of entertainment.

When radio comes along in the 20s and television comes along in the 50s, the agencies are actually very involved not just in producing the ads but in producing the programmes. There’s a very blurred line between ads and programmes in the early days of both those media. And yet, even within the advertising agencies, you can tell that a lot of people are uncomfortable with that.

“This is a cheap business and I don’t want it,” as a character says in The Hucksters.

One other thing that then happened which added a new dimension to this, is around the 1960s and around Bill Bernbach. Agencies found a different way of making themselves feel special and professional which was a bit more sexy and a bit more cool than just being the rational persuaders and this was this idea of creativity – a word that was never very clearly defined but seemed to stand for some sort of quasi-artistic quality that agencies were brilliant at and which could only really be appreciated by other people in advertising. It began to drift away, from that point, from the public.

For a long time this was relatively harmless. It might even have been, in some ways, a positive thing. But I think that like some sort of very slow growing tumor or something this has now grown in the last couple of decades to being so dominant that it has taken over the way the advertising business thinks of itself. So we now have the situation where for many people in advertising the idea of being too popular is just something they shy away from and certainly creative awards have played quite a key role in in this process.

It’s not something that’s happened overnight, it’s not something you can put down to to one single factor, but it has now grown to being a dominant discourse that that means there’s quite a gulf between what a lot of agencies think they ought to be doing and the world of popular culture.

JACOBS: Do you think that these days agencies are just rather disconnected from what consumers think about things?

FELDWICK: Yeah I think there’s a lot of evidence that people who work in agencies tend to form a very homogenous and very particular group who share a lot of cultural values which are on the whole quite remote from a great deal of the country and this has been well documented elsewhere that they are accused of being elite and based around the Capital rather than the regions and certainly that there is a class thing here that is quite marked. I made a throwaway remark in an interview with Campaign which they then put on the front cover about the difference between Fleabag and Mrs Brown’s Boys and in various ways this proved to be quite controversial because Mrs Brown’s Boys stands for everything that elite group would not want to touch with a barge pole and yet it’s hugely popular. It was the best-selling Christmas video a couple of years ago and it attracts huge audiences and it is very much a part of that carnival, musical, popular entertainment tradition which the industry has become increasingly wary of touching.

JACOBS: We seem to have got to a point where we’re completely obsessed with short term measures and things like that as opposed to sort of building brands over the over the long term. Do you think that, as we move towards more short-term media forms and addressable advertising and things that just wish you to react really quickly, do you think the separation of media from creative makes that whole situation worse? Is now a good time to talk about maybe them coming a bit closer together again?

FELDWICK: I agree with you certainly that short termism is another thing that’s been well documented and much talked about. It’s difficult to know how one really shifts that because if its roots are right at the core of what a business is trying to do, then it’s very difficult to make that argument that building a brand is a good thing. I was looking at evidence recently that brands that are owned by venture capital companies are not really interested in the long term and you can see that their share prices don’t go up because they’re not planning for the long term. They don’t care because that’s not what they’re in it for. They just want to rank up the short-term profits and and then sell it on.

So if there is a short-term attitude right at the heart of a business but of course you know not all businesses are like that, but those who want to be building for the long term, I think there is a very strong case to be made for branding and Mark Ritson recently wrote something I thought rather good about this thing. It’s actually quite difficult to persuade a board but it can be done and it does require a lot of skills on the part of the CMO to do that. But I think that is one great divide that needs to be addressed by whatever means. And, of course, in terms of the other point about creative and media, I really can’t make an argument that says why they should be kept apart – whatever bringing them back together might mean.

I think it’s something that we should all be thinking about and certainly one important aspect of that is – not so much in the level of you know because we are putting this ad here this is how you write the ad (although that may be a part of it) – it’s more to do with how both those both those skills are looking at the same reality and looking at the same information and are addressing the same needs, that they are both addressing the same task of brand building and they’re both looking at the same sort of data, the same sort of information and they are working within that same framework. That used to be much more the case when when creative and media were together in the same agencies.

I suppose the intention behind account planning and its origins, whether it was realised or not, was very similar to what you’re trying to do at Crater Lake which it was always saying there is more and more information and data around but it is not being brought together, it is not being coordinated and it’s not being used in a holistic way and I think at its best we were able to do that at BMP and at JWT media planning and account planning were very very close and that brought the whole thing together. The planners were the people who were pulling all the data sources together and interpreting it and helping to make sense of it which is which is precisely what we’re doing now. I think that perennially remains something that’s important to do. So yes I think whatever it means bringing creative and media back together is something that is probably overdue.

NEXT WEEK: Tammy Charnley, General Manager, Marketing, Suzuki

PREVIOUS EPISODES:

THREE: Abba Newbery, CMO, Habito

TWO: Nick Emery, founding partner, You & Mr Jones Media

ONE: Prof Karen Nelson-Field, founder of Amplified Intelligence